How is it that a tiny postage stamp, costing but a few coins, perhaps only one, can perform such a remarkable feat—taking your message to the very ends of the earth perhaps? And who gets the money represented by the stamp, since the letter may well traverse a number of different lands to reach its destination?

These questions you might enjoy having cleared up, as well as others such as, How did the present international postal system come into existence? What steps are being taken to improve and widen its usefulness?

The Early Stages

Early history tells of courier systems among the Persians, the Romans, and the Incas of South America, organized for the sole purpose of governmental communication. There was then no provision for the ordinary citizen. And besides, very few citizens could even read and write, so as to take advantage of such means of communication.

Some factors that worked together to produce a sudden upsurge in the demand for communication were: the discovery of the western hemisphere, with its consequent spread of population; the advent of printing; and the great widening of opportunities for education. To meet this demand, Franz von Taxis introduced an international postal service in the sixteenth century. It operated between and among a limited number of European states. This exchange of mail was governed by international agreements—not one overall convention, but rather a number of bilateral treaties.

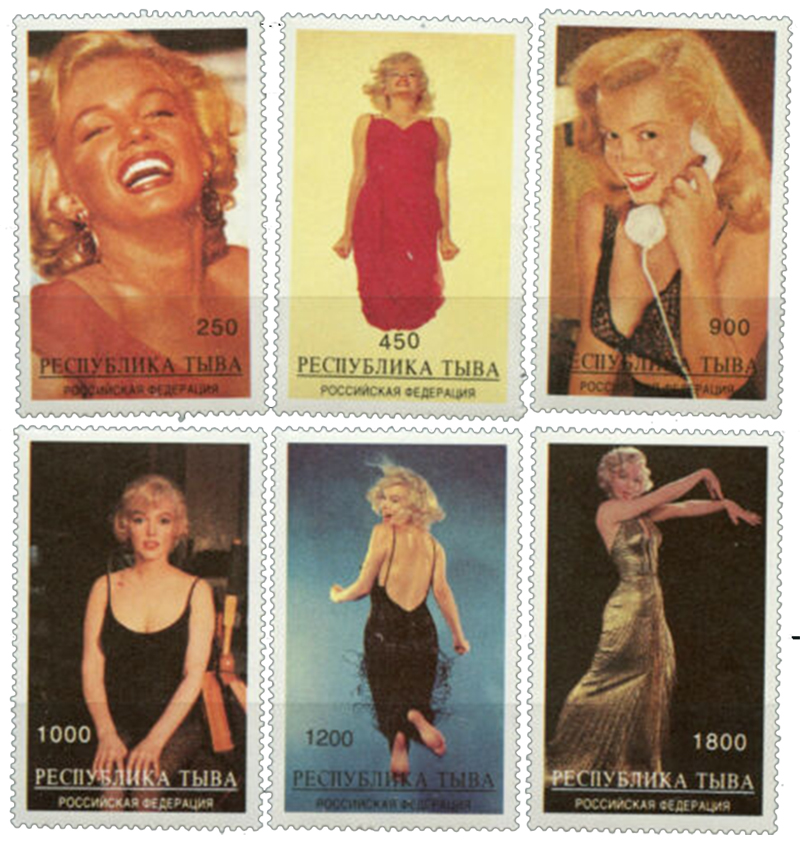

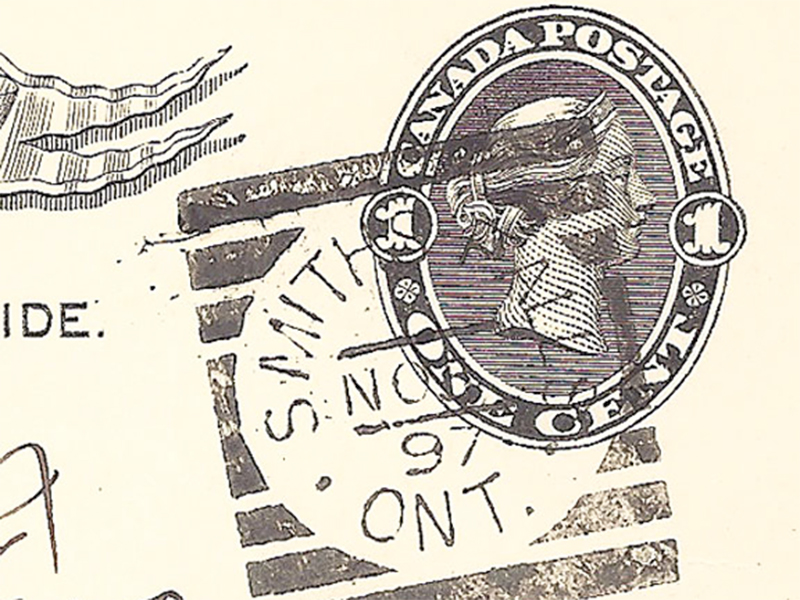

The era of steamships and railroads brought low-cost transportation of private mail, and greatly spurred the growth of communication by letter. Postal administrations became aware of the need to standardize their methods and charges and to simplify the formalities involved. Introduction of “penny postage” in Great Britain in 1840 and the creation of the postage stamp by Rowland Hill were steps in the right direction.

It is strange, is it not, to think that up to the middle of the nineteenth century United States mail was operating without benefit of postage stamps or envelopes as we know them? The letter sheet was simply folded into itself securely and the address written on the outside. Usually the last fold was fastened with sealing wax. The mailing charge was paid at the post office, and the amount stamped on the outside of the letter.

Another forward step came in 1863, when, at the initiative of Montgomery Blair, postmaster general of the United States, fifteen European and American countries had their representatives convene at Paris with a view to widening the scope of international postal arrangements.

Founding of the Postal Union

The great need, now, was for an overall international convention or agreement. The outline for such a postal union with plenipotentiary powers was drawn up by a high-ranking official in the postal administration of the North German Confederation. On the invitation of Switzerland, a conference was called in Berne in 1874. Delegates from twenty-two states quickly reached an agreement that has since been known as the Berne Treaty.

Thus the General Postal Union was born, coming into force on July 1, 1875. The accession of many new member states suggested a more appropriate name, which was adopted three years later, namely, the Universal Postal Union.

The twenty-fifth anniversary of the Union’s founding was duly commemorated in Switzerland by the erection of an imposing monument—a globe raised high on rough-hewn granite, with dainty figures, representing international communication, circling the globe and passing letters from hand to hand. Thousands of persons visit the site every year.

For some seventy years admission of new members to the Union was by unilateral declaration, but at the Paris Congress of 1947 this provision was amended, Thereafter applications were to be processed by the Swiss government, and then presented to the members. At least a two-thirds approval was required before an applicant could be admitted. The 1964 Congress in Vienna provided that any member of the United Nations could accede to the Union simply by formal declaration to the Swiss government, and without need of the two-thirds vote of approval.

General Principles

The simplicity of the Union’s rules has vastly contributed to the smooth running of the organization. As a fast-growing public service organization, it pursues altruistic aims, and despite political upheavals and international conflict, it manages to keep functioning with considerable success.

The basic Act of the Union is the Constitution that sets forth the aims and lays down precise rules entitled “General Regulations.” In connection with these rules, some elasticity in practice is allowed in each member country.

Member countries are considered as forming “a single postal territory for the reciprocal exchange of letter-post items” and they have “guaranteed freedom of transit within the territory of the Union.”

Charges to be collected by member countries have been standardized, and the sharing of charge between the country where the mail originates and the country of its destination has been abolished. Thus, since 1875, the land of origin retained the entire charge levied by them, and the land of destination was no longer remunerated for the distribution of postal items.

This principle is based on the assumption that a letter invites a reply, thus balancing the accounts of total mail. It is a generous and practical policy, leading to simplification and economy for all member countries.

But conditions have altered considerably since 1874, when one could properly speak of “reciprocal exchange.” The increasing volume of “AO mail,” that is, mail items other than letters, postcards, air letters and letter packages, led some countries to suggest a revision at the time of the Tokyo Congress of 1969. A new provision resulted, namely, that any member country whose weight of incoming AO mail exceeded its outgoing AO mail would receive a compensation “of 50 gold centimes per kilogram” for the difference. This goes into effect July 1, 1971.

The Union’s Constitution provided for an Executive Council, for an assembly or congress of its members every five years, and for an international bureau.

How the Union Functions

The Congress is the supreme authority in the Union, having duties that are largely legislative. It is in principle convened every five years. It cooperates closely with the Executive Council and attends to such matters as revising the Acts of the Union as and when developments warrant such changes. Sixteen ordinary Congresses have been held to date, and have introduced many conveniences for the public, including the sale of money orders, free postage on literature to the blind, and so on.

The agreement concerning postal subscriptions to newspapers and periodicals, concluded in Vienna back in 1891. The International Bureau, maintained in Berne, Switzerland, collects information and dispenses information and counsel to any administration desiring it. It is also responsible for development of postal technical assistance, and may even be called on to serve as arbitrator. The costs of its maintenance are shared by the members of the Union. just recently it has moved into a new and larger building in a suburb of Berne.

The Executive Council, a permanent body, is composed of thirty-one member countries. Its responsibility is to ensure the continuity of the Union’s activities from one Congress to another. It works closely in conjunction with the International Bureau.

The Swiss Confederation functions in the role of Supervisory Authority, having powers relating to financial activities, organization and administration of the International Bureau. It is also the official depository of the Acts of the Union, and has certain legal powers with respect to membership.

Work of the Congress

To keep up with the swiftly changing world scene, each Congress of the Postal Union has a very heavy program. The XVth Congress, held in Vienna in 1964, for instance, had 140 sessions. Its 500 delegates examined and voted on 1,160 proposals.

The XVIth Congress, convened in Tokyo in 1969, was the first to be held in Asia. There were 523 delegates, representing 132 of the 142 member nations. It heard and voted on hundreds of proposals. Its decisions will have important effects on the 550,000 post offices around the world, and for the 4,500,000 persons employed in handling the more than 250,000 million postal items per year for inland and foreign transit.

Step into a modern post office and observe the great number of services available to the ordinary citizen. Money orders can be purchased for either a domestic or foreign destination. Then, there are parcel post and C.O.D. provisions. Also, one can register and insure letters and parcels so as to guarantee delivery—a most important feature when the mail item is either valuable or urgent.

Most large urban centers around the world, and many smaller towns, enjoy at least two mail deliveries per day—deliveries right to the home or place of business. Only within comparatively recent times air transport of mail has helped to speed up the delivery of letters and small packages to a fantastic degree. Now one can receive a letter mailed at a point two or three thousand miles away within forty-eight hours of the time of mailing!

For many years now the railroads have contributed to the speed and efficiency of the mails. Special railroad cars allow for sorting of mail even as the train speeds on its way, day and night, to some distant point. At some small wayside stations letter-post mail is dropped off without a stop. More than that, with the help of an ingenious crane, mailbags can also be picked up by the moving train.

So there is much more to the delivery of your letter than what you may see in your local post office. Mail pickup, mail sorting and bagging, and routing of the mailbags for speed, are only routine matters involved in the worldwide network of postal facilities. Is it not remarkable that you can sit down and write a letter to someone on the other side of the planet, with reasonable expectation that your letter will reach the addressee, even if he or she is a prisoner of war or a civilian internee? And, generally speaking, your letter will be inviolate. Very few countries have the staff or the inclination to censor the vast volumes of mail that pour in from day to day.

By reason of the Union’s operations the postal rates are within the ability of most persons to pay. And though political and economic limitations prevent your visit to some relative or friend in a far-off land, warm personal correspondence can help to maintain the bonds of family or friendship.

The speed and efficiency of the well-mounted courier of Persia called forth the admiration of Herodotus, the Greek historian. His expression included these words, now inscribed above the entrance of the General Post Office in New York city: “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” Even while you sleep, your mail is speeding on its way.

Factual Source:

JW Online Library

Leave a Reply